By James Flanders (City University, London) and Maddy Thompson (Keele)

In March, most Universities announced an end to on-campus teaching. Drawing on our differing experiences as a final year student (James) and lecturer (Maddy) doing a Geographies of Digital Health module, we reflect on some of the critical challenges and opportunities that this swift transition has created. Despite our differing experiences, we hope our overall reflection will be useful to students and staff embarking on or returning to online teaching.

The Perils of the Digital

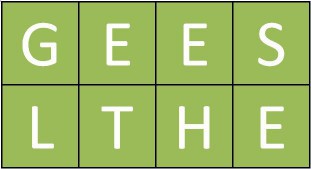

Coincidentally, the transition to online teaching began with a lecture on Digital Health geographies. Previous planning dictated that this would include an interactive activity with students communicating via digital technologies to produce a presentation from opposite ends of a lecture hall to experience distanced health. The need for students to go online made this a more realistic experience. Figure 1 illustrates the students’ reflections on distanced and digital work. The issues and opportunities identified are applicable to our broader experiences of online teaching. Here we focus on communication and technology.

Communicating Online

As the Geographies of Health students identified, online communication is complicated. More communication is required to make up for what is lost without face-to-face interaction. This meant more emails. We both felt compelled to have push notifications on 24/7 to prevent email build-up and inevitable confusion. Online teaching makes it harder for students and staff to ‘switch off’.

Online communication in teaching settings creates additional problems. For example, Maddy’s early lectures over-ran. She was more concerned with speaking slowly and repeating key points where she would usually have gestured. Online communication requires additional time to communicate the content; hence, there is less time for content.

If students can easily switch between the lecture and external information (websites, videos, quizzes, etc.), then less content is required in lecture form. James, with a laptop and tablet, was able to easily view the lecture on one screen and take notes and undertake research on his other (see Figure 2). Students confined to using a single device cannot. We both firmly believe that universities should provide complimentary tablets/laptops to students who enrol. To give all students a better opportunity to engage with online teaching equally.

Pre-recorded lectures may be attractive for many staff and reduce the risk of over-running, but for James and his peers, live lectures are essential to maintain motivation and a sense of ‘being there’. Maddy also found the live lectures preferable for this reason, particularly as she was able to gauge understanding through using the ‘react’ option on Microsoft Teams chat (see Figure 3).

In some sessions, we shared open dialogue at the end of each lecture. This allowed us to have a friendly and unstructured discussion between ourselves. Due to the unprecedented times, this was beneficial to restore a bit of normality in the storm. However, while James had the technology available to go on video, others did not.

Issues of privacy and accessibility meant students had a choice to be on camera, and chat functions were used for discussion. This necessitates multiple forms of conversation, and for Maddy as moderator, created additional challenges. It is easy to prioritise students that can be seen and heard, but care should be taken to ensure this does not happen. For students like James, who were willing and able to share an insight into their home lives, these discussions were more enriching than talking in lecture halls. However, lower engagement reduces the chance of diverse opinions from entering the teaching space.

Interestingly, many issues disappeared in one-to-one video calls. These more personal meetings provided a greater sense of normality as we could focus on body language and engage in natural forms of speaking. Furthermore, there are fewer connectivity issues with fewer people on a call, mainly as smartphones can be used. Students were much more likely to use video in this smaller setting.

The transition to online teaching necessitated a steep technological learning curve for us both, particularly due to the multiple options available and lack of planning time to plan. Maddy used various options as university preferences changed, but James was subjected to countless more across different modules. Innovative forms of online teaching are additional things for students to learn. They can quickly become a technological burden.

Additionally, while our experiences were mostly trouble-free, key issues on accessibility and engagement arose. It became clear that Zoom is smoother than Microsoft Teams, less likely to be impacted by poor connectivity. The features of Teams, however, are better suited for group work, and the slide above was produced via students in chat groups. As groups could call in Maddy and other teaching staff, it also helps produce a feeling of normality.

The future of HE Geography teaching

Covid-19 has created striking new norms and associated challenges. Our experiences highlight two overarching concerns universities and teaching staff must address to ensure equality in learning and teaching.

- More uniformity among online teaching across modules, courses, and universities.

- This reduces the demands of training for both staff and students and reduces complexity in learning and teaching environments.

- Teaching staff should also consider their own technological practices to avoid over-burdening students for innovation’s sake.

- Universities must provide students with additional technology to ensure that those confined to single devices are not excluded from learning opportunities.

- As online communication is more time consuming and creates additional challenges relating to equality, diversity and inclusion for students, staff need to ensure their teaching practices (such as in group discussion) are inclusive.